Driving Hard vs. Driving Home: The Grumpy Old Engineer’s Guide to Steel Grade Selection (API 5L & ASTM A252)

Look, I’ve been doing this since before some of you were born. I’ve seen piles snap like twigs because some project manager in a clean office wanted to save twenty bucks a ton on steel. I’ve also seen rigs hammering away for hours on end, shaking the neighbors’ houses, because the specified grade was tougher than a two-dollar steak and wouldn’t budge.

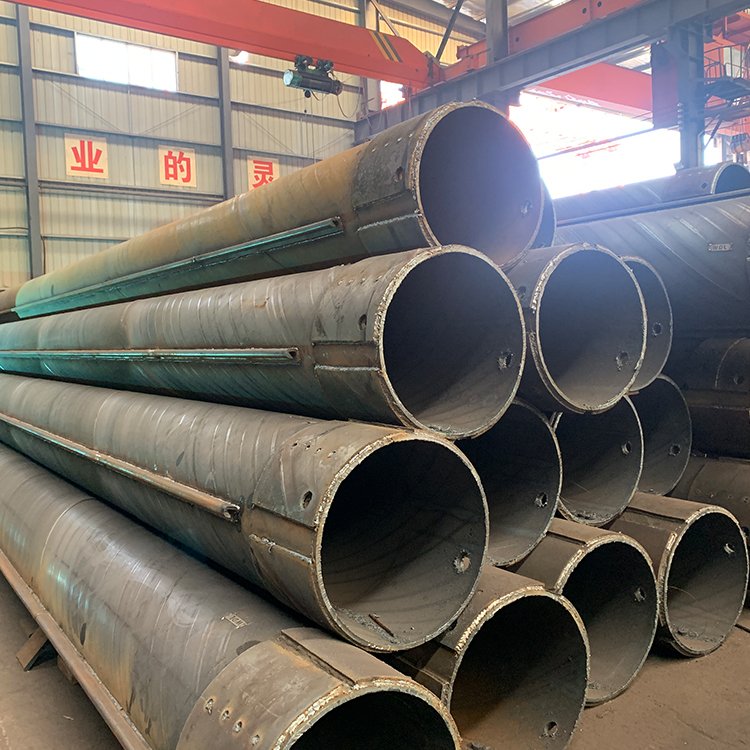

We’re talking about pipe piles. Specifically, how the steel grade—that little number on the mill cert like Grade 2, Grade 3, or even the high-strength API 5L X70—affects the core fight of foundation engineering: Can we get it down to the depth we need without destroying it, and once it’s down, can it hold the load?

If you’re looking for a simple textbook answer that says “higher grade = better,” you’re in the wrong business. You might as well pack up your rig now. This isn’t just about stress-strain curves; it’s about the rock band down the street, the hidden boulder three feet down, and the look on the welder’s face when he sees the chemistry of that pipe.

The Alphabet Soup of Standards (ASTM A252 vs. API 5L)

First, let’s get the paperwork straight. I still see specs that call out “ASTM A252 Grade 3,” and then in the next paragraph, they reference “API 5L X42.” It happens all the time. They are kissing cousins, but not twins.

-

ASTM A252: This is the granddaddy of pipe pile standards. It’s broad. It’s forgiving. It was written specifically for piling. They care about the diameter, the wall thickness, and the tensile strength. But here’s the thing old-timers know: A252 allows for some slop in the manufacturing. The chemistry isn’t as tight as API. It’s meant to be driven into the ground, not necessarily to hold pressure.

-

API 5L: This is pipeline steel. It’s meant to hold natural gas at high pressure. The metallurgy is tighter. The carbon equivalent (CE) is usually more controlled because you have to weld it in the field without preheating sometimes. When we use API 5L for piling (which happens a lot when there’s surplus pipe or specific grade requirements), we are essentially using a Cadillac as a tractor.

Table 1: Common Grade Equivalents and Yield Strength

| Designation | Specified Min. Yield Strength (SMYS) | Typical Application Mindset | My Personal Field Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASTM A252 Grade 2 | 35,000 psi (241 MPa) | “The Old Faithful” | Bends before it breaks. Great for rock. Welders love it. |

| ASTM A252 Grade 3 | 45,000 psi (310 MPa) | “The Workhorse” | The industry standard. Good balance, but stiff. |

| API 5L X42 | 42,000 psi (290 MPa) | “The Hybrid” | Similar to Grade 3, but better weldability due to lower carbon. |

| API 5L X52 | 52,000 psi (359 MPa) | “The Muscle” | You feel this in the hammer. High capacity, but brittle if you’re careless. |

| API 5L X70 | 70,000 psi (483 MPa) | “The Specialist” | Rare for piling. Needs kid-glove handling. One bad hit and it’s scrap. |

The Core Trade-Off: Structural Fy vs. Drivability

Why do we care about the grade? It comes down to two equations we all have stuck to the inside of our hard hats.

1. The Structural Capacity (The “Why it holds”)

For a pile in pure end-bearing, the allowable load is largely a function of the steel’s yield strength.

(Note: I use 0.5 for a rough safety factor. Don’t @ me with LRFD phi factors; this is napkin math.)

If you have a 12.75-inch diameter pipe with a 0.375-inch wall (that’s your standard stuff), the cross-sectional area of steel is roughly 14.5 square inches.

-

Grade 2 (35 ksi): Capacity = 0.5 * 35,000 * 14.5 = ~254 kips

-

Grade 3 (45 ksi): Capacity = 0.5 * 45,000 * 14.5 = ~326 kips

That is a 28% increase in load capacity just by changing the paper on the material. The pipe looks the same. It weighs the same. But suddenly, one pile can do the work of 1.28 piles. For a project manager looking at a lump-sum bid, that is pure gold. Fewer piles, cheaper cap, faster schedule.

2. The Driving Stress (The “Why it breaks”)

Here is where the rubber meets the road—literally. When you hit a pile with a diesel hammer, you send a stress wave down the steel. The maximum compressive stress during driving can be approximated (very roughly) by:

…but in the real world, we use wave equation analysis. But the gut-check rule I use? You don’t want to exceed 90% of the yield strength during driving if you value your sanity.

High-grade steel (like X70) has a high yield, so theoretically, you can hit it harder. But here is the trap that catches the young engineers: Ductility vs. Brittleness.

Grade 2 steel is like taffy. If you hit an obstruction, the pipe might “mushroom” at the tip. It might bend. But it rarely just shatters. Grade 3 is stiffer. High-strength low-alloy (HSLA) steels like X70? They have a much finer grain structure. They have less “give.” If you hit a boulder at a slight angle with an X70 pipe, you aren’t bending it; you are splitting it. I saw it happen in Seattle in 2018. Spec called for high-strength pipe to handle the seismic overturning moments. They hit a glacial till layer with a embedded cobbles. Crack. Just like that. The pile split up the side for 20 feet. Repair cost more than the pile.

Personal Anecdote: The Louisiana Dock Fiasco

Let me tell you about a dock job in Baton Rouge. Soil was soft clay for 60 feet, then a dense sand layer. We needed high capacity for the crane loads. The geotech report was solid. The structural engineer, a sharp kid but fresh, specced API 5L X60. High strength, so fewer piles. Sounded great.

We set up the first test pile. 24-inch diameter, 1-inch wall. Heavy stuff. We start driving. Blow count is 10 blows per foot in the clay. Boring. Then we hit the sand. Blow counts jump to 100, then 150 blows per foot. We are approaching refusal according to the Wave Equation Analysis Program (WEAP) results. The hammer is bouncing.

Then, thud. Not the sharp ring of steel-on-steel. That dull thud that makes your stomach drop. We pull the hammer, look down the pipe. The pile didn’t buckle, but the welder notices a hairline crack at the weld seam of the pipe itself. The base metal had micro-fissures. The high strength, high carbon equivalent steel had been hammered so hard it work-hardened and fractured at a microscopic inclusion.

We switched to Grade 3 for the rest of the job. Lower capacity per pile? Yes. But we added one more pile per bent. Did it cost more? Maybe in steel tonnage. But we didn’t have a single crack after that. The “lower grade” steel absorbed the abuse. It dented slightly at the tip, but it never fractured. The Grade 3 let us drive “home” instead of just driving hard.

The Weldability Factor (The Field Reality)

We talk a lot about driving, but we don’t talk enough about the guy with the stinger.

High-grade steel (X52 and above) often has a higher Carbon Equivalent (CE). The formula is:

If that number creeps above 0.45, you are in a world of hurt. You need preheat. You need low-hydrogen rods. You need to control interpass temperature. On a barge in the winter, with wind blowing 20 knots? Good luck.

I’d rather drive a slightly lower capacity Grade 2 pile and know the splice weld is sound than drive a rocket-ship Grade 3 pile and have the splice snap during driving because the heat-affected zone (HAZ) turned into glass.

Table 2: The “Grumpy Engineer” Field Selection Matrix

| Condition | Recommended Grade | Why? (The Field Logic) |

|---|---|---|

| Easy soil, high loads (Urban infill) | A252 Grade 3 | High capacity, but soil is predictable. Low risk of damage. |

| Rock / Glacial Till (New England / Midwest) | A252 Grade 2 | Let the steel deform. It’s cheaper to replace a bent tip than a shattered pile. |

| Offshore / Marine (Gulf Coast) | API 5L X52 | Need the strength for batter piles and lateral loads. Pipe is heavy, hammer is bigger, and welders are specialists. |

| Arctic Conditions | Special low-temp (API 5L X42 or X52 with CVN testing) | Brittle fracture is real when it’s -40°. Charpy V-Notch tests are worth their weight in gold here. |

| Contractor Self-Perform (Low Bid) | A252 Grade 2 | If I don’t trust the welders, I don’t trust the high-grade steel. Grade 2 forgives sins. |

The Data Corner: What the PDA Tells Us

We use the Pile Driving Analyzer (PDA) nowadays to check stresses. It’s a black box that gives us numbers we used to guess at.

I ran a job where we drove a 30-inch Grade 2 (35ksi) pile and a 30-inch Grade 3 (45ksi) pile of the same wall thickness in the same soil profile.

-

The Grade 2: PDA showed a maximum compressive stress of 42 ksi during driving.

-

Analysis: That is 120% of yield. Technically, overstressed. But we checked the pile, saw a slight “hourglass” shape near the tip, but no rupture. The steel yielded locally, absorbed the energy, and kept going.

-

-

The Grade 3: PDA showed a maximum compressive stress of 48 ksi during driving.

-

Analysis: That is 107% of yield. In theory, safer than the Grade 2’s percentage. But the pile had a visible “ring” to it. It was ringing like a bell. That’s elastic strain energy. When that pile finally hit refusal, the stress wave reflected and caused a tensile crack at the top.

-

The data showed the Grade 3 was “safer” on paper, but the behavior of the Grade 2 was actually more resilient. The Grade 2 sacrificed itself to save the pile. The Grade 3 held its shape but transmitted destructive energy.

Solving the “Brittle Pile” Failure

So, how do we fix it when high-grade fails?

-

Cushioning is King: If you have to use Grade 3 or higher in tough ground, you cannot use a bare steel anvil. You need a micarta or aluminum/bronze cushion in the hammer. You need to lengthen the pulse. You need to slow down the energy transfer.

-

Tip Reinforcement: I’ve started ordering “drive shoes” for high-grade piles. A thicker ring of steel (often a lower grade, actually!) welded to the tip. It takes the abuse, deforms, and protects the expensive high-grade pipe above it.

-

Pre-augering: If you know there’s a boulder layer, don’t be a hero. Drill a pilot hole through the hard layer. It costs time, but it’s cheaper than replacing a pile.

-

The “Two-Hammer” Method: Start with a smaller hammer to get it through the overburden. Get the tip seated past the hard layer gently. Then bring in the big hammer to drive it to final penetration. This prevents the initial overstressing that causes micro-cracks.

Trends and the Future (The Green Steel Nonsense)

I’m seeing a push for “Green Steel” now. Steel made with electric arc furnaces and higher scrap content. The chemistry is sometimes all over the place. The yield strength might hit the mark, but the residual elements (copper, tin) can cause issues during driving—something called “hot shortness” if you ever need to do a flame cut.

The latest trend in 2024 is a move back to API 5L X42 for standard piling. It’s a happy medium. It has the yield close to Grade 3 (42ksi vs 45ksi) but with the controlled chemistry of pipeline steel, meaning it welds better and has better toughness. I’m seeing a lot of spec sheets in Texas and Florida moving away from A252 entirely and just calling out API 5L X42 with a specific wall thickness. They are paying a bit more for the steel, but saving on inspection and repairs.

Conclusion: Don’t Be a Hero

If you take one thing away from this rambling, let it be this: Don’t let the structural engineer’s calculator bully the pile hammer.

High-grade steel (Grade 3, X52, X70) gives you the numbers on the takeoff sheet. It makes the math easy. But the ground doesn’t read the math. The ground hits back.

I’ve learned to look at the local geology first, pick the grade that can survive the drive, and then calculate the capacity. If that means I need a few more piles of Grade 2, so be it. I sleep better knowing the piles are actually in one piece down there, rather than a shattered high-strength tube leaking its guts into the water table.

Pick the steel that can take a punch, not just the one that looks good on a spreadsheet. That’s the trade-off. That’s the job.