Open-Ended Pipe Piles: Why We Leave the Bottom Open (And When It Saves Your Bacon)

By a Field Engineer Who’s Seen Too Many Closed-Toes Fail

You know, I get this question a lot from young engineers fresh out of school. They’re standing on site, looking at this big steel pipe hanging off the crane, and they see the bottom is just… open. Nothing there. Just a steel cylinder with a sharp edge ready to hit the dirt.

And they always ask the same thing: “Uh… shouldn’t we cap that? Won’t dirt get inside?”

Bless their hearts.

If I had a dollar for every time I heard that question, I’d retire to Florida and never look at another pile driving rig again. But it’s a fair question if you’ve only ever dealt with concrete piles or H-piles. The open-ended pipe pile looks wrong if you don’t understand what it’s actually doing down there.

So let’s set the record straight. Open-ended pipe piles aren’t a design oversight. They’re not a cost-cutting measure where we ran out of steel plate. They’re a deliberate choice—sometimes the only choice—when the ground gets nasty.

And here’s the kicker: sometimes leaving the end open is the difference between a foundation that lasts fifty years and a pile that buckles before it hits refusa

First Things First: What Are We Actually Talking About?

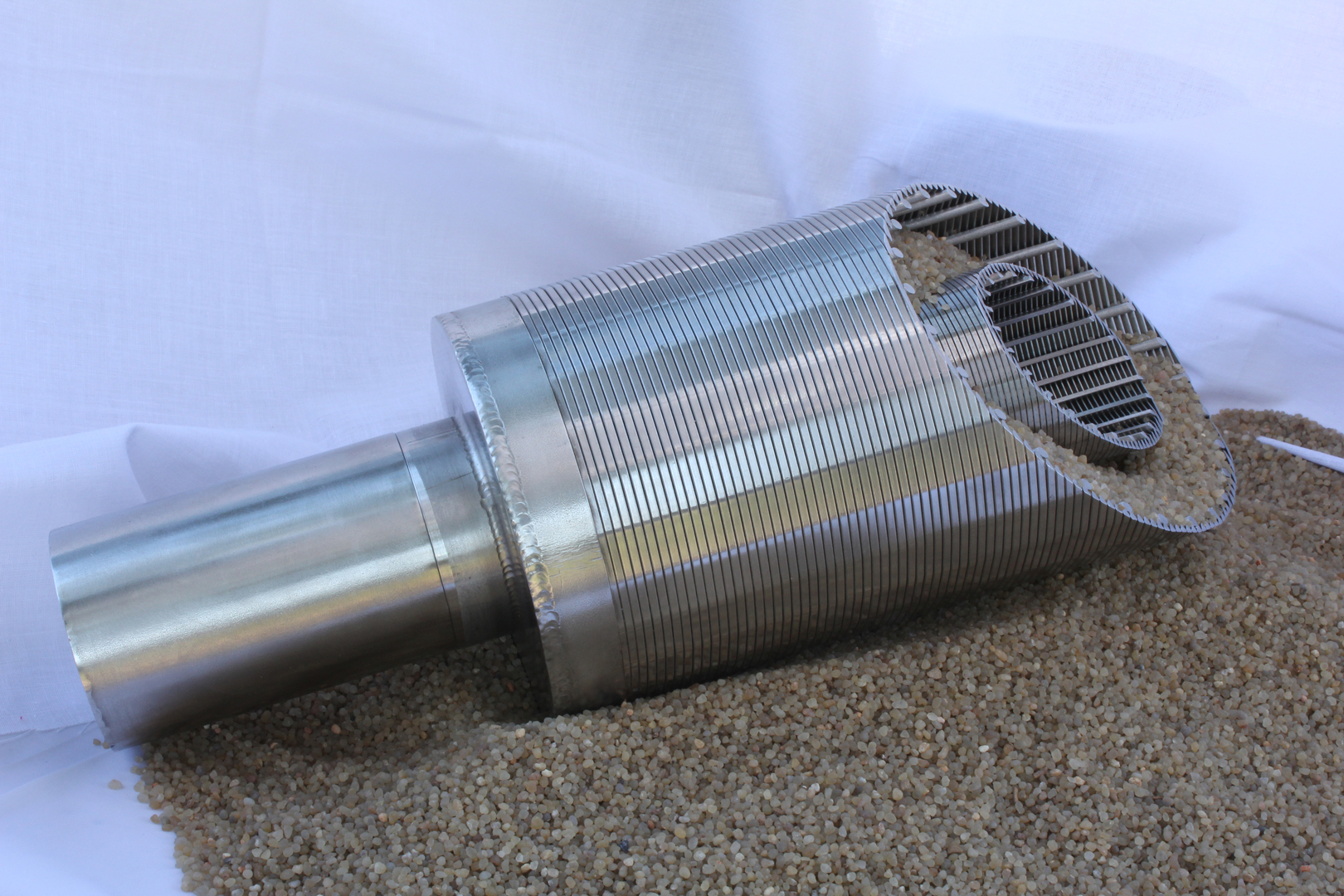

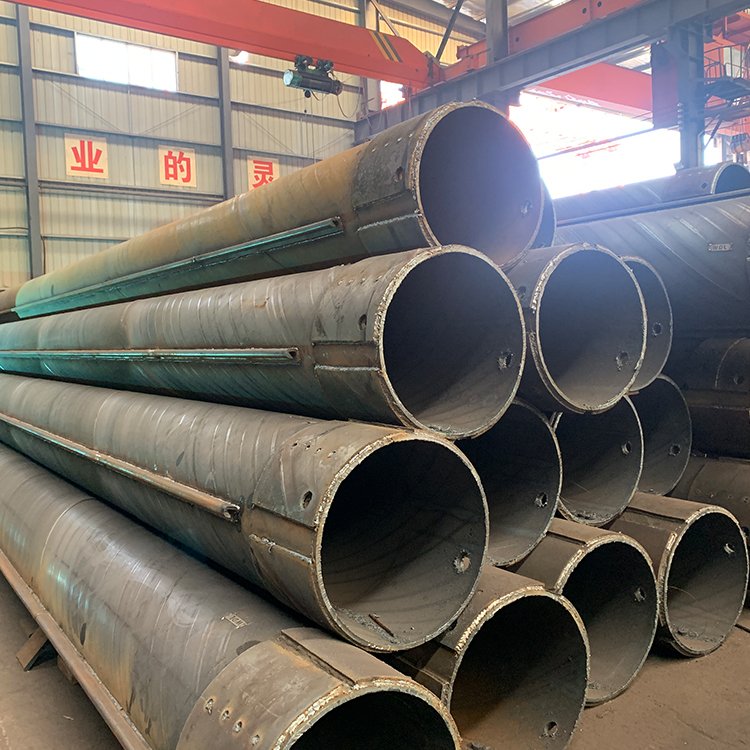

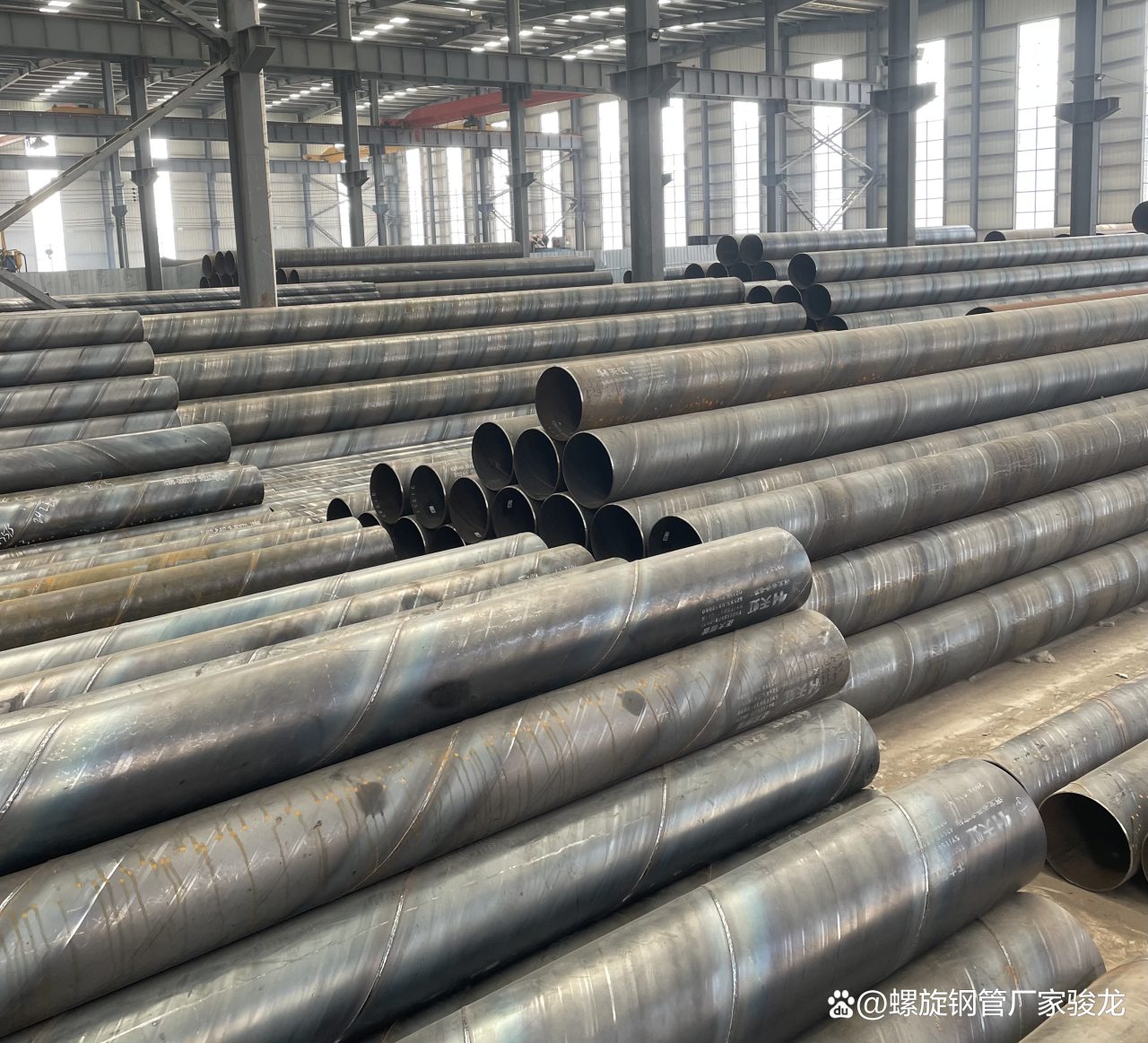

An open-ended pipe pile is exactly what it sounds like. Steel pipe. Driven into the ground. No shoe. No plate. Just a hollow cylinder with a cutting edge at the bottom.

The soil doesn’t get pushed aside like it does with a closed-end pile. Instead, it enters the pipe. Forms a soil plug inside. And that plug—that column of dirt trapped in the steel—becomes part of the structural system.

Simple concept. But the mechanics? That’s where it gets interesting.

The Basic Physics: Why Open vs. Closed Matters

Let’s start with the fundamental difference. When you drive a closed-end pipe (or any solid pile), you’re displacing soil. You’re pushing it out of the way. That takes energy. It creates resistance. It can also heave the ground around you, lift adjacent piles, and generally cause headaches for everyone on site.

Open-ended? The soil has somewhere to go. Inside the pipe.

The governing equation—the one I scribble on coffee-stained notebook pages—looks something like this:

Where:

-

R_outer shaft is the skin friction on the outside of the pipe

-

R_inner shaft is the friction between the soil plug and the inside wall

-

R_annulus is the bearing at the tip (the steel itself, not the plug—just the ring of steel at the bottom)

Notice what’s missing? End bearing on a solid plug. Because initially, there isn’t one. The soil moves up inside as you drive.

But here’s where it gets weird. At some depth, that soil plug stops moving. It jams. It locks up. Now you’ve essentially created a closed-end pile, but the soil inside is stressed, confined, and acting differently than the soil outside.

That moment—when the plug locks—is critical. It determines everything about how the pile behaves under load.

The Soil Plug: Your Uninvited Tenant

I remember a job in Mobile, Alabama back in ’09. We were driving 36-inch open-ended piles for a ship berthing structure. Dense sand, some layers of stiff clay. Textbook conditions for open-ended.

First test pile goes in. We’re monitoring with PDA. Everything looks normal. Then we hit about 45 feet, and the blow counts jump. Not gradually—straight up. Thirty blows per foot becomes a hundred and fifty in the space of three feet.

We pull the hammer, look down the pipe with a light. That soil plug? Solid as concrete. Locked tight. We couldn’t even get a sampling tube through it.

That’s the plugging phenomenon. And it’s why open-ended piles can actually end up with higher capacity than closed-end in some soils.

The plugging ratio—what the academics call the Incremental Filling Ratio (IFR)—is something we track religiously:

If that number drops below 80%? You’re getting plug development. Below 50%? That plug is locked. Below 20%? You’re basically driving a closed-end pile now, whether you intended to or not.

And here’s the thing: a plugged pile behaves differently under load. The load transfers down through the steel, but also through that soil column. The interface friction on the inside mobilizes. You’ve got double the surface area working for you.

Table 1: Open-Ended vs. Closed-Ended Pipe Pile Comparison

| Parameter | Open-Ended | Closed-Ended | My Field Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Installation Ease | Easier in dense soils | Harder—full displacement | Open-ended punches through; closed-ended fights every inch |

| Ground Heave | Minimal to none | Can be significant | In tight clusters, open-ended saves your survey control |

| Inspection | Can inspect inside after driving | No visual access | Found a void in limestone once by looking down the pipe—saved the job |

| Material Cost | Same pipe, less tip fab | Need plate to close end | Open-ended saves maybe $200 per pile on fab |

| Driveability | Better in obstructions | Worse—hits like a battering ram | Open-ended will sometimes skewer a boulder; closed-ended just stops |

| Capacity Mechanism | Combined friction + plug | End bearing + friction | Both can achieve similar ultimate capacity—just different paths |

| Typical Use | Marine, deep foundations, rock sockets | Onshore, easier ground | If I’m offshore or near water, I’m open-ended nine times out of ten |

When Do We Actually Use Open-Ended?

Scenario 1: Marine Construction (The Classic Case)

You’re building a dock. Or a pier. Or a dolphin for ships to tie up to. You’re in the water. The soil is variable—maybe sand, maybe soft clay, maybe some layers of stiff material. And you can’t see the bottom.

Open-ended is your friend here.

Why? Because you can’t predict exactly what you’ll hit. There might be boulders. There might be old construction debris. There might be a layer of calcareous sandstone that shows up on the boring logs but in reality is fractured and variable.

I drove piles in San Francisco Bay back in the early 2000s. Old industrial area. The borings showed clean sand. What we actually hit? Timber piles from an old pier, chunks of concrete, a car axle (I’m not kidding), and a layer of shell hash that reflected the hammer wave so bad we thought the pile was breaking.

Open-ended pipe sliced through most of that. A closed-end pile? Would’ve stopped cold at the first obstruction.

Scenario 2: Penetrating Dense Layers

Sometimes you need to get through a hard layer to reach bearing depth. Maybe it’s glacial till. Maybe it’s a dense sand stratum. Whatever it is, it’s tough.

Open-ended pipe has a smaller effective tip area. Just the steel annulus. So the driving resistance is lower. You can punch through layers that would stop a closed-end pile cold.

The math is simple enough:

For a 24-inch pipe with 1-inch wall:

- Closed-end tip area = π × (12²) = 452 square inches

- Open-end steel area = π × (12² – 11²) = about 72 square inches

That’s one-sixth the area. One-sixth the end bearing resistance during driving. You’ll drive through that dense layer while closed-end piles are still bouncing the hammer.

Scenario 3: Rock Socketing

This is where open-ended piles really shine.

When you need to socket into rock—drill or drive into bedrock—you want open-ended. Why? Because you can clean out the inside. You can drill through the plug, extend the socket, and actually inspect the rock at the bottom.

I did a job in Kentucky where the bedrock was weathered limestone with solution cavities. Closed-end piles would’ve been a disaster—they’d either stop on a pinnacle or punch through into a void with no warning.

Open-ended? We drove to refusal, then used an airlift to clean out the inside. Shone a light down there. Could see the rock condition, the voids, everything. We even sent a camera down once. That’s not possible with closed-end.

Scenario 4: Displacement-Sensitive Sites

Here’s one the textbooks don’t emphasize enough.

If you’re driving piles close together—like for a mat foundation or a high-density cluster—ground heave becomes a real problem. Closed-end piles displace soil. That soil has to go somewhere. It goes up. It moves sideways. It lifts previously driven piles.

I watched a job in Boston where the contractor used closed-end pipe in a tight grid. Three days later, the first piles were two inches higher than when we drove them. Had to redrive every single one. Cost a fortune.

Open-ended? Minimal displacement. The soil goes inside the pipe. The ground around stays put. Your survey control stays happy. Your client stays happy. You stay employed.

The Failure Modes (And How to Fix Them)

Let’s be honest: open-ended piles aren’t magic. They fail. I’ve seen it. You’ll see it if you do this long enough.

Failure Mode 1: The Rat-Hole

This happens in loose sands or soft clays. The soil plug doesn’t develop. It just keeps running up inside the pipe. You drive fifty feet, and the soil inside is fifty feet deep. No plugging. No inner friction development.

Why it matters: Your capacity is way lower than you calculated. You’re relying only on outer skin friction and maybe a little tip bearing on the steel annulus.

The fix: Stop driving. Let it sit overnight. Sometimes the soil sets up and gains strength. Or—and I’ve done this—pump a low-strength grout plug at the bottom to create an artificial end bearing. It’s a补救措施, but it works.

Failure Mode 2: Sudden Plug Release

Scariest sound in pile driving.

You’re driving along, plug locked, blow counts steady. Then wham—the pile drops six inches with one blow. The plug released. Suddenly you’re fifty blows per foot and then ten. The whole load path changed.

Why it matters: If you don’t catch this on PDA, you’ll think you’ve hit a weak zone. You’ll keep driving. The plug might lock again deeper, but you’ve lost the data correlation. Your capacity estimates are garbage.

The fix: Watch the driving records like a hawk. Sudden drop in blow count? Check the plug level. If it dropped, you’ve had a release. Recalculate everything.

Failure Mode 3: Buckling During Driving

This one’s rare with heavy wall pipe, but I’ve seen it with thinner walls in very dense soil.

The pile is open-ended. The soil plug locks. Now you’re driving a closed-end pile effectively, but the wall is thin. The driving stresses concentrate at the tip. Boom—local buckling.

The fix: Heavier wall at the tip. Drive shoes. Or switch to a smaller hammer. Sometimes the problem isn’t the pile—it’s the contractor trying to drive too fast with too much energy.

Table 2: Typical Open-Ended Pipe Pile Applications by Region

| Region | Common Application | Soil Conditions | Why Open-Ended Works |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gulf Coast (USA) | Marine docks, fender systems | Soft clays, sands, occasional shell layers | Variable conditions; need to penetrate shell without stopping |

| Pacific Northwest | Bridge foundations, seismic retrofits | Glacial till, cobbles, dense sands | Can punch through cobbles that would destroy closed-end tips |

| Southeast Asia | Reclamation projects, port facilities | Loose sands, coral fragments | Coral is brutal on closed-end—open-ended cuts through |

| Great Lakes | Mooring dolphins, breakwaters | Stiff clays, bedrock near surface | Easy to clean out for rock sockets |

| Middle East | Offshore platforms, jetty structures | Calcareous sands, weak sandstone | Calcareous materials degrade with driving—open allows inspection |

The Inspection Problem (And Why It Matters)

Here’s something nobody talks about in the design office.

With closed-end piles, you’re flying blind. You have no idea what’s happening at the tip. Did it hit something? Is it damaged? Is it bearing on a boulder instead of bedrock? Good luck figuring that out.

Open-ended gives you options.

I always spec open-ended for critical piles because I can inspect after driving. Drop a light. Send a camera. Measure the plug. Sample the material at the bottom.

In Miami, we had a project where the spec called for rock sockets. Contractor drove closed-end test piles. Static load tests passed. Great. Then production started, and suddenly piles were failing at half the test load.

Turns out, the limestone had solution cavities. Some piles were bearing on a thin crust with void underneath. Closed-end couldn’t tell us that. Open-ended? We’d have seen the cavity when we cleaned out the plug.

We made them switch. Cost overruns. Lawsuits. The whole mess. All because someone wanted to save a few bucks on fabrication.

The Grumpy Engineer’s Rules for Open-Ended Pipe Piles

After thirty years, I’ve got some rules. They’re not in the codes. They’re not in the textbooks. But they’ll keep you out of trouble.

Rule 1: When in doubt, leave it open.

Unless you have a compelling reason to close the end—like you need end bearing on a hard layer immediately and can’t risk plugging—just leave it open. You have more options later. You can always grout the inside. You can always drive a mandrel. You can always add a plate after driving if you really need closed-end behavior. But you can’t un-close a closed-end pile.

Rule 2: Monitor the plug.

Every ten feet, check the plug level. Mark the inside with a weighted tape. Know what your plug is doing. If it’s not developing, adjust your capacity estimates. If it’s locking early, expect higher driving stresses.

Rule 3: Don’t trust the boring logs.

They’re a guess. An educated guess, but still a guess. Open-ended piles handle the surprises better. When the log says “sand” and you hit boulders, you’ll be glad the end is open.

Rule 4: Clean it out if you need end bearing.

If you’re relying on end bearing in rock or dense material, clean the plug. Drill it out. Air-lift it. Don’t assume the plug will transfer load forever. In cyclic loading—like in seismic areas or marine environments—that plug can loosen over time.

Rule 5: Consider the corrosion.

Inside matters too. Open-ended piles have interior surface area that’s exposed to air, water, or soil. In marine environments, that interior can corrode faster than the outside. I’ve seen 1-inch wall pipe turn into swiss cheese inside because nobody thought about the inside corrosion. Coat the inside if you can. At least think about it.

Recent Trends: What I’m Seeing in 2024-2025

The industry’s changing. Slowly, but it’s changing.

Larger diameters are becoming common. I’m seeing 60-inch and 72-inch open-ended piles now for offshore wind foundations. The mechanics are the same, but the scale changes everything. That soil plug weighs tons. Cleaning it out requires serious equipment.

Monitoring is getting smarter. We’re using fiber optics now—strain gauges along the length, inside and out. Watching how the plug loads the pile in real-time. The data is incredible. We’re learning that our old assumptions about plug behavior were sometimes wrong.

Hybrid systems are appearing. Drive an open-ended pile, clean it out, insert a reinforcement cage, and fill with concrete. You get the driveability of open-ended steel with the capacity and corrosion resistance of concrete. Smart. I like it.

Environmental regulations are tightening. In some areas, you can’t drive closed-end piles anymore because of the ground displacement. Too much risk to adjacent structures. Open-ended is becoming mandatory in urban infill projects.

The Case Study That Keeps Me Humble

Let me tell you about a job that almost ended me.

New Orleans. 2017. Floodwall replacement. Spec called for 24-inch closed-end pipe, 80 feet deep, battered piles for lateral resistance. Standard stuff.

First day of driving, the very first pile hits refusal at 40 feet. Can’t move it. Hammer’s bouncing. We pull it—tip is crushed. Bent inward like a soda can.

Turns out, there was a buried concrete mattress from an old levee repair. Nobody knew about it. No historical records. No mention in the geotech report. Just random concrete at 38 feet.

We switched to open-ended. Drove right through it. The open end cut into the concrete, fractured it, pushed pieces aside. Soil went inside. We cleaned it out later, drove another ten feet into the native clay, and passed the load test with flying colors.

If we’d stuck with closed-end? We’d still be out there, probably, beating our heads against concrete and wondering why we chose this profession.

The Numbers: Quick Reference

Typical Dimensions I Use:

- Wall thickness: Minimum 0.5″ for 24″ diameter, scale up with size

- Tip bevel: 30-45 degrees on the outside, leaves inside square

- Splices: Full penetration butt welds, sometimes with backing rings

Capacity Estimates (Rough—Don’t Build Without Analysis):

For a 24″ × 0.5″ open-ended pile in dense sand:

- Outer skin: 2-3 kips per foot

- Inner skin (if plugged): 1-2 kips per foot

- Tip (steel only): 50-100 kips depending on density

- Total ultimate: 300-500 kips typical

For the same pile closed-ended, you might get 400-600 kips, but you’ll never drive it as deep. Trade-offs everywhere.

The Bottom Line

Open-ended pipe piles exist because the ground isn’t a textbook. It’s messy. It’s unpredictable. It hides boulders and old car axles and concrete chunks from projects fifty years ago.

Leaving the end open gives you options. You can drive through stuff that would stop a closed-end pile. You can inspect after driving. You can clean out and socket into rock. You can grout for extra capacity. You can do all of it, or none of it, depending on what you find down there.

Are they right for every job? No. If you’ve got clean soil conditions, good bearing layer at consistent depth, and no inspection concerns, closed-end might be simpler and cheaper.

But if you’re working in unknown ground—and let’s be honest, when do you really know the ground?—open-ended is the safer bet. It’s the difference between guessing and knowing. Between hoping the pile’s okay and actually seeing it.

And in this business, I’ll take seeing over hoping every single time.